Why Democrats can’t sell a strong economy, in 3 charts

The red shift in 2024 was so extensive that no domestic issue tipped the vote in favor of President-elect Donald Trump. However, another important factor may have been the widespread economic dissatisfaction of the electorate.

The persistence of pessimism about the US economy has surprised political analysts, as most of the main indicators suggest that it is strong and that the US has recovered better than other countries from the recession caused by the epidemic. Inflation has fallen sharply from its peak in June 2022, reducing the rise in the price of basic goods. The Federal Reserve began lowering interest rates, making borrowing cheaper. The economy has continued to grow at a solid pace. Unemployment fell to a 54-year low in 2023 and remained at a desirable level.

On paper, everything looked good. But in poll after poll before the election, voters have expressed concern about the economy and put inflation as their top issue. Negative, early voting data from exit polls showed a similar trend.

At the heart of that disconnect may be factors that broad economic indicators often struggle to capture: Despite a “strong economy,” many Americans continued to feel burdened prices are high, he struggles to find work, and he takes on a lot of debt. And the results on Election Day suggest they blamed Democrats — particularly President Joe Biden and Democratic Vice President Kamala Harris — for those problems.

Here’s what the rosy economic picture received by Democrats may be missing.

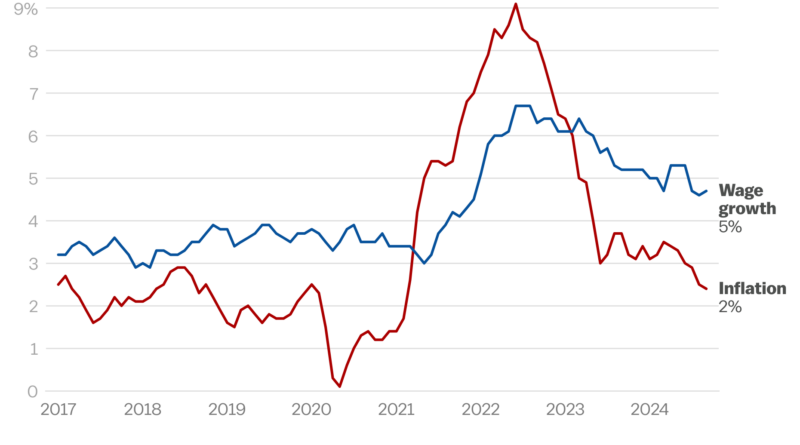

There has been a real disruption of inflation

Although inflation has fallen to 2.4 percent from a post-pandemic peak of 9.1 percent, it has been clear for months that Americans are still hurting financially and emotionally.

Wage growth has lagged behind inflation on average. But wage gains have not been the same: Low-wage workers have seen some of the biggest gains, particularly in the leisure and hospitality sectors, but other industries, from advertising to chemical production, have seen their wages fall in line with inflation.

Nicole Narea/Vox

But even if the workers got a raise that exceeded inflation, that doesn’t help panic the stakes. Research has shown that consumers have an internalized “reference price” – an idea of what is a good price for the goods they buy regularly. If that perceived price doesn’t match reality, consumers feel short-changed.

Although the price of a person can change, it usually does so slowly, according to the average rate of inflation (about 2 percent per year). Consumers haven’t had much time to adjust amid the rapid inflation of recent years. That makes them push inflation too far: An August YouGov survey found that many consumers think inflation is much higher than it actually is.

Consumers also often do not understand how inflation works. The important thing to know is that it only goes one way: When inflation decreases, that only means that prices are increasing faster, not that they are falling. (That can happen, though rarely.)

Falling prices, also known as deflation, can be a sign of economic distress. If consumers pay less for a good, that can translate into less money to pay the workers who produce and distribute it, leading to lower overall consumer spending and slower economic growth.

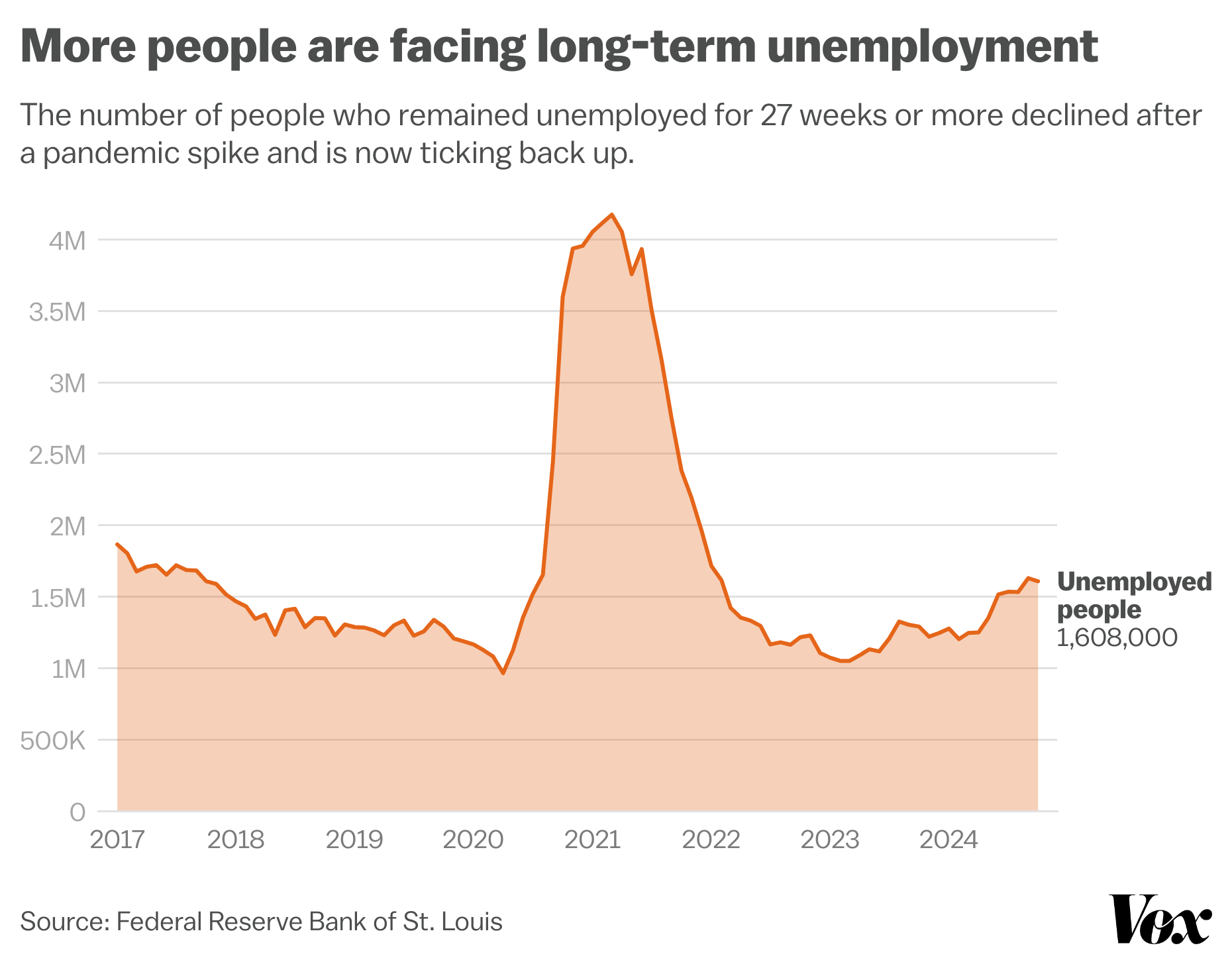

The job market is tougher

The days of the pandemic’s “Great Resignation” — when employers struggled to hire and workers had their own choice of jobs and the ability to demand higher wages — are over. The unemployment rate has risen in recent months to 4.1 percent, and job growth has slowed to levels not seen since 2020.

This is still within the range that economists would consider unemployment to be low. But the top rate doesn’t tell the whole story.

For one, people are staying out of work longer: 1.6 million Americans were out of work for at least 27 weeks in October, compared with 1.3 million in the same month last year.

Nicole Narea/Vox

Many workers may also find themselves unemployed, engaged in part-time work or work that does not require training or qualifications. This is especially true for recent college graduates, more than half of whom were unemployed a year after graduation, according to a February report by the Burning Glass Institute and the Strada Institute. of the Future of Work.

Other industries are also cutting jobs. That includes jobs in manufacturing and temporary help services, which fell by 577,000 from March 2022.

The overall unemployment rate does not necessarily reflect these factors, suggesting that the working life of Americans may not be as rosy as the top job numbers make it out to be.

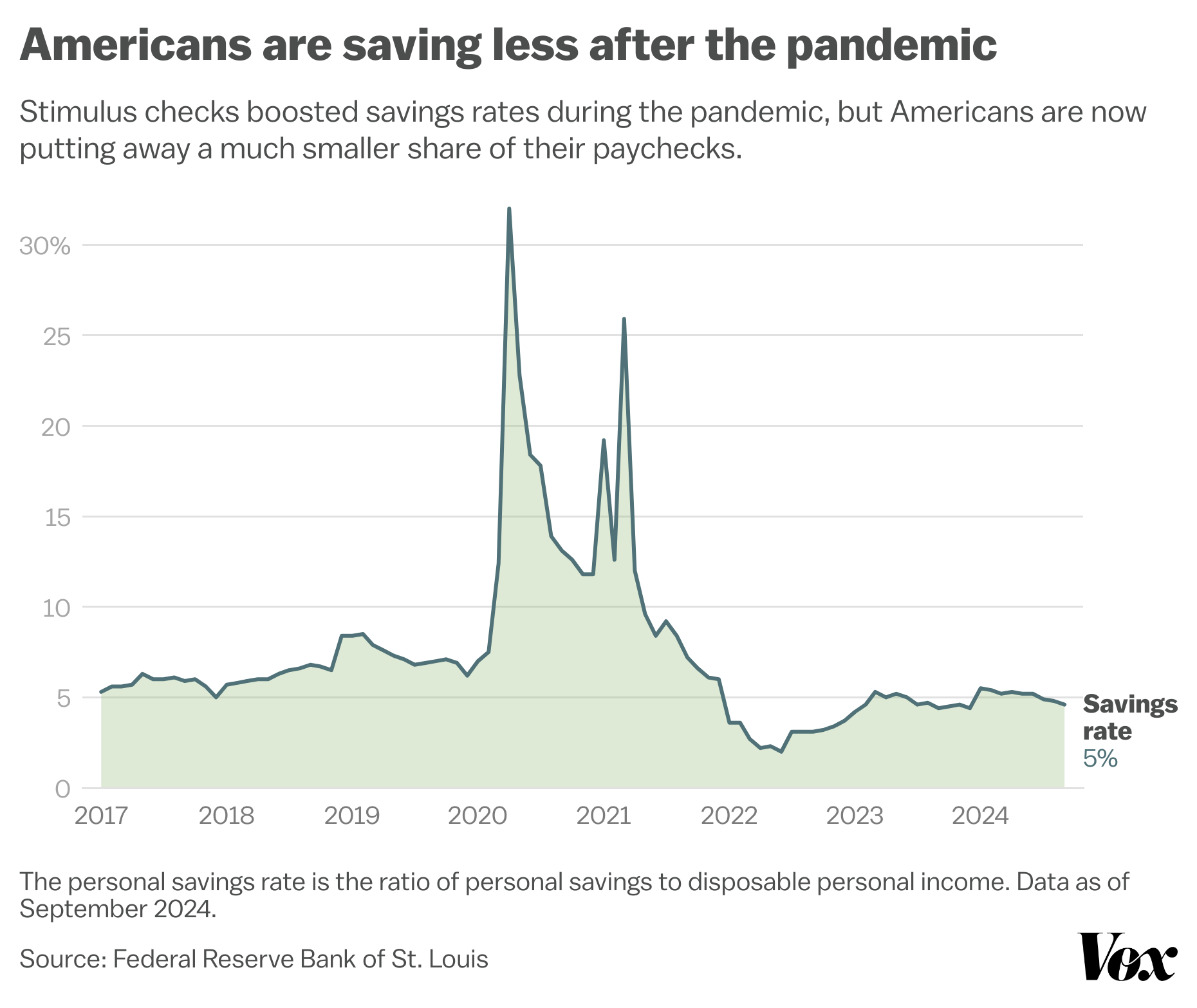

Americans have less money and take on more debt

After a spike in prices during the pandemic due to a series of stimulus checks, Americans are now saving less than they were before the pandemic. This creates a cycle where Americans have less money, so they borrow more. As interest rates have been high, borrowing has become more expensive, leaving them with even less money.

Nicole Narea/Vox

Americans are drawing on their depleted savings and piling up debt with credit cards and other revolving credit plans in which consumers can borrow money repeatedly up to a set limit and then pay it off. in stages. Total credit card debt in the US hit an all-time high of $1.14 trillion as of October, with individuals owing as much as $8,000.

Credit card delinquency rates are on the rise. Young people in particular, many of whom are also struggling with high student loan debt, are falling behind on their credit card payments. Sometimes, something has to give.

This may be the reason that many Americans are still longing for the economy under Trump in 2019, when they had more money and were not facing so much debt.

#Democrats #sell #strong #economy #charts